Table of Contents

Student Experiences

So what have your fellow anthropology enthusiasts been up to all this time?? Here are just a few statements from some of your peers.

Interested in participating in the same field schools or internships that they did? Feel free to contact them to get the “insider” scoop.

| Name | Year | Program | Picture |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kenny Chiou | NYU '10 | Tiputini Biodiversity Station, Ecuador / Ometepe Biological Field School, Nicaragua |  |

| Michelle Goodson | NYU '10 | Archaeology Field School (Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi) |  |

| Victoria Grefiel | NYU '10 | Independent Fieldwork, New York City |  |

| Natalia Guzman | NYU '10 | San José de Moro Archaeological Project (Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú) |  |

| Kate Randall | NYU '11 | Dacian Fortress and Acropolis, Romania |  |

| Morgan Turnage | NYU '10 | Abomey Plateau Archaeological Field School (University of California - Los Angeles) |  |

| Ashley van Batavia | NYU '10 | Field Assistant, Bolivia / Primate Behavior and Conservation Course (SUNY Oneonta) |  |

| Jesse Wolfhagen | NYU '11 | Cueva Negra del Estrecho del Rio Quipar, Spain (University of Murcia) |  |

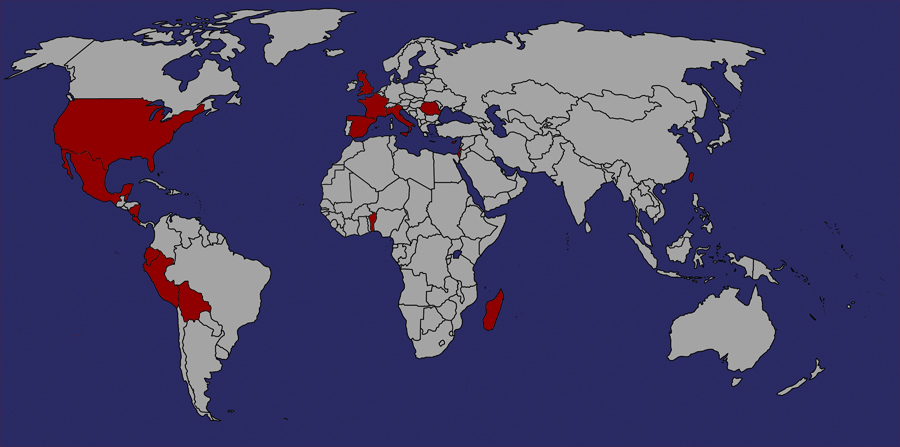

Map of countries around the world where our present and past contributors have made a mark

Kenny Chiou

NYU '10

In summer 2008, I attended a field school at the Ometepe Biological Field Station in Nicaragua. Ometepe is an island in the middle of Lake Nicaragua and, in addition to about 30,000 people, it is home to large populations of white-throated capuchin (Cebus capucinus) and black mantled howler (Alouatta palliata) monkeys. At the field station, I took a class entitled Advanced Primate Behavior & Ecology. The “advanced” part of the name signified a greater emphasis on independent research projects. We were required to attend lectures on field techniques only (none on behavioral ecology), helping budget more time for developing the project and collecting data. I would recommend this course over the course entitled Primate Behavior & Ecology for those applying to either Ometepe or La Suerte who have any sort of background in primate behavior because the more time you can spend in the field, the better it is for your project. Also, traveling from the field station to the forest was generally a long walk and returning to the station to attend lectures in the afternoon effectively ended the workday prematurely. In fact, after getting accustomed to the fieldwork lifestyle, it became common practice to pack breakfasts and lunches just so that we were able to stay in the forest the entire day.

I applied to work at Ometepe because, first, I love the outdoors and was intrigued with working in tropical forests and second, I had some interest in primate behavioral research and wanted to find out if I was suited for work in the field. I also applied for and received a grant from the Dean’s Undergraduate Research Fund. As it turns out, field school provided exactly what I had anticipated. It provided a taste of the demands of field research while providing guidance and support when needed. And fieldwork can certainly be demanding. At Ometepe, wake up times between 4:00 and 5:30 in the morning were the norm. Hiking several miles a day was essential just to travel between the field station and the forest. Once in the forest, we were exposed to a variety of insects and malicious plants that no amount of bug spray could fix. At the same time, however, the professor, TA’s, station staff and other students were always nearby. Food was always provided and water was easily accessible. The living quarters were quite comfortable. We even had time before bedtime to screen movies and hang out! In short, the field school was demanding at times but definitely not as much as it could have been. Students who decide that field research is not for them—and some students definitely do—should never be left to agonize over the duration of their stay; for people like me—those who are not confident about their career interests and goals—field school is very worthwhile for this reason. My experience at Ometepe was positive and convinced me to return to the field the next summer as a field researcher at Yasuní National Park, Ecuador.

Michelle Goodson

NYU '10

During Summer 2009, between my Junior and Senior years at NYU, I attended an 8-week intensive Archaeology Field School at Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi (TAMU-CC). My decision to attend field school is probably one of the best decisions I have made thus far, as the experiences learned are infinitely applicable to my future in the field of Anthropology. I would highly recommend to students who are interested in Archaeology or Physical Anthropology to attend a field school, as it will qualify students for Cultural Resource Management work as well as many other jobs that require practical excavation experience. Additionally, field work is now a prerequisite for most graduate programs in Anthropology.

It is important to know what kind of experience you are looking for when you decide upon a field school. During my search I knew that I wanted to test myself; I wanted to place myself in conditions that would challenge me and create a make-or-break scenario so that when I left the field school I would know whether or not I would be happy with digging and field research as a career. With these thoughts in mind, and the notion that I preferred to stay within the country, I chose the Archaeological Field School of South Texas, a field school located in San Patricio, Texas: Population 318.

While this field school fit my desires for a challenging environment (we slept in tents, temperatures were constantly in the triple digits, and we bathed in outdoor showers with cold water), there were several other aspects of the school that attracted me. The AFSST was run through and accredited university (Texas A&M University Corpus Christi) and offered 6 credits to attend the school. This was important to me, as I wanted to transfer the credit and have a field school on my academic transcript (be sure to petition before you go!). Additionally, AFSST was run by a professional archaeologist, Dr. Bob Drolet, a Professor at TAMU-CC and Curator at the Corpus Christi Museum of Science and History. These connections with a museum and University was a terrific aspect of the school, as it allowed students to learn exactly how materials and discoveries get from the dirt in your trowel, all the way to a museum display or the classroom.

I also knew, when applying for field schools, that I wanted to learn it all: excavations, mapping, lab work, data analysis, everything. I knew that in order to do this and make my time worth it, I needed to find a field school that was as long as possible- providing me with as much time as possible to absorb all that I could. There were very few field schools that lasted longer than 5 weeks, and this 8-week AFSST program provided me with the unique opportunity to not only do it all, but to do it all several times and genuinely learn. By the end of the season, I felt as though I was an Archaeologist and that I had the skills I needed in order to hold my own on any other dig.

By far, the best trait of the AFSST was the fact each student had to write a paper. While this isn’t typical of a field school, this was something I knew I wanted. The papers that the students of the AFSST wrote were based on a formulated thesis started at the beginning of the 8-week program and developed through data collected at the site. But even better than the formulation of the paper was the fact that students were given the opportunity to present their findings at a professional conference (Texas Archaeological Society Meetings) in October. The process of writing this paper helped me to better understand what kind of work is necessary to achieve a finished product good enough to present to an academic community. Not only was this process priceless, but the networking and the practical experience of presenting a paper was beyond invaluable.

Victoria Grefiel

NYU '10

One of the biggest draws for me to come to NYU was the city itself―a place that is dynamic, always progressive, yet still remembers and honors its history. New York City contains within its limits, spaces with differing characters that somehow fuse together to make a remarkable and unique fabric of diversity. Walk down an avenue and it is a bustling hub of activity, but turn into a street and it is a quiet block with trees growing in small, assigned plots on the sidewalk and beautifully designed buildings standing shoulder to shoulder. Chinatown, Soho, Greenwich Village, Tudor City, Harlem―each has something to offer those willing to tread through their streets. If you just stop and listen to the city, it can teach you a whole lot more life lessons that you will ever find in your textbooks.

As a Cultural Anthropology major, I could have gone to a foreign country to conduct my fieldwork, but why do so when the city has countless numbers of untold stories that it is more than willing to share? The growing relevance of urban ethnography as a field of study is another reason to make the city your own field school. Living in the epitome of urban centers, one can be an insider yet still feel like an outsider. Conducting fieldwork in the city can be quite tricky but you can bet you will always learn something new about the city and its people. To date, I have studied social life at a Barnes and Noble bookstore, observed Friday prayers at a mosque, and examined language use among several ethnic groups. My most recent project is a study of how Filipino-Americans who arrived in the United States as children are or were socialized into the American society. Again, the city plays a big part in my research. Conducting interviews and participant observations with Filipino-Americans who live in the city has helped paint a fascinating yet complex picture that can add nuances to the story of the American immigrant experience.

I could have gone to a field school based in the forests of the Amazon or in the desserts of North Africa, but truth be told, I would probably have perished due to the environment before I could have learned something useful. I am a city girl through and through. I give props to those who can weather the heat and the itches at said field schools; it takes a tough person to endure such difficulties. But, even if it is of a different caliber, I think it takes a tough person to be able to study and live in the city.

Natalia Guzman

NYU '10

If you are thinking about becoming an anthropologist, attending a field school as an undergraduate student is probably one of the smartest things you can do. It is guaranteed that you will gain priceless knowledge there. At the very least, you will learn if the career you saw yourself pursuing as an anthropologist is actually what you want to do for the rest of your working life. Of course, the actual field school you pick is quite important since the programs that different institutions run can be structured in different ways. Fortunately, the program I was part of was very organized and not only did I learn a lot, but I also met wonderful people who I still keep in contact with.

The field school I attended this past summer was the San José de Moro Archaeological Project, run by Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú. I was part of an international group of students who had been accepted to the program. The program starts in Lima, where students get acquainted with each other and also learn more about the program. Next, we traveled by bus to the San Jose de Moro archeological site. While we didn’t live at the site, we were staying in a town only 5-10 minutes away by car. Our work day normally started at 7AM and concluded at 5 PM. At the site we were taught the technical aspects of archaeology. We also kept field journals where we recorded what we did each day and also described findings. In the weekends we would visit other archaeological sites nearby which were sometimes being excavated by different archaeological programs. A couple of times a week we would hike mountains in order to prospect archaeological sites. In those occasions we were taught to use GPS devices and given the tasks of using them to mark the archaeological sites.

Overall, my experience with this program was fantastic; everything was well-planned and you never found yourself bored. Additionally, after the program concluded I decided to go to Cusco and Machu Picchu with a group of friends I made during field school.

Kate Randall

NYU '11

In summer 2008, I spent five weeks working on a dig in Transylvania, Romania. It was my first field experience, and I was immediately immersed in the hands-on nature of life in the field. The program I chose was the Dacian Fortress and Acropolis dig, an excavation of an Iron Age fortress in the foothills of the Carpathian Mountains. I applied for, and was honored to receive, a Ranieri Travel Grant to support my work on this dig.

Camping for those weeks in Transylvania was an experience unlike any other. Exciting and exhausting days at the site, unforgettable nights around the campfire or in our tents listening to the night noises of the mountains. The first days of the excavations were tough for me- I'd never been on a dig before, had no idea what to do, and somehow managed to get hit in the head with a shovel. All my previous archaeological experience had taken place in a nice comfortable laboratory or classroom. But I learned fast, with the help of the professionals and the other volunteers. Excavating the fortress made me feel personally acquainted with the history of the region; we found weapon fragments, jewelry, and pottery made by both the native Dacians and the Romans who had invaded Dacia in the late Iron Age. A favorite find was part of a Roman chariot wheel.

In our time off, we'd hunt for fossils in the river, hike the foothills, or make the long trek by foot to the nearby village of Racos. Weekends involved trips into the cities of Brasov, Bran, or Sighisoara, to see the archaeology museums (and of course, Dracula's castle!). Getting to know another country, working with archaeologists of countless different nationalities and backgrounds, and being exposed to life in the field combined to make this an incredibly valuable experience.

Morgan Turnage

NYU '10

During the past summer, I attended the University of California at Los Angeles Field School in Benin, West Africa. After flying into the port town of Cotonou, we spent a couple of days getting acquainted before driving to our house, an apartment between the two towns of Abomey and Bohicon. Benin doesn't yet have an extensive history of archaeological research, so we were one of only a few groups trying to fill in the rather large historical gaps. We excavated at five separate sites, the first four focusing on rural areas, with the intent of showing different living standards between the king's palaces and the commoner's abodes. The last site was a palatial site on which the current king was building a new palace. Due to this restriction this site became a salvage project, one week to remove as much as possible before the king kicked us out. The kingdom of Dahomey ruled here and participated heavily in the slave trade, not only enslaving populations around them, but sometimes even their own people. Subsequently the artifacts we uncovered were a mixture of European and West African goods, ranging from pipe pieces to glass beads to iron ritual scepters.

On a typical day we would wake up at 5 AM to get out to the site and work before the hottest part of the day. We excavated until 2 PM and then returned home, dirty and sweaty to wash our artifacts, a task which usually consumed 3 more hours. For all of the effort put in we got so much more out of the program. We were able to help survey the area, in addition to identifying diagnostic traits in the pottery we were uncovering. Field school aren't just work though. We spent our weekends going on trips around the area, hiking and interacting with the people who I found to be quick at inviting you into their homes. After pottery washing we would ride zemijohns (motorcycle taxis) into town to wander through the market or spend the afternoon taking a walk on a small dirt trail leading into the bush.

For a student hoping to become an archaeologist it is extremely important to visit a field school. Excavating can be hard work and not everyone enjoys it. There is precision to it, technique. You can't just dig a hole and you don't always find something. Sometimes one more piece of precious pottery looks just like another thing to have to wash. I enjoyed my field program and have made lasting friendships not just with the other American students but also with Beninois students and farmers who helped us at the site. It was an amazing experience.

Ashley van Batavia

NYU '10

This past summer I volunteered as a field assistant studying Bolivian gray titi monkeys for Kimberly Dingess, my professor from the Primate Behavior and Conservation field course I took through SUNY Oneonta. The site where I studied was located on the outskirts of Santa Cruz, Bolivia and each morning I woke early in hopes of finding my titi monkey group after they woke up. Titi monkeys are quite shy, which made studying them hard during my first few weeks since the titis would flee at the sight of me. However, it was important not to get frustrated and I was rewarded for my persistence as the monkeys slowly began to stay and rather then runaway they would vocalize and soon they became habituated – no longer responding to my presence. This experience was a great opportunity for me to get a better assessment of fieldwork and I recommend anyone who thinks they want to go into studying wild primate behavior to do volunteer fieldwork to get a better sense of all that it involves.

Jesse Wolfhagen

NYU '11

I spent the summer of 2009 working at a field school in Murcia, Spain. The field school lasts for three weeks in July, though you could stay up to six weeks, and took place in a rock shelter cave site: Cueva Negra del Estrecho del Rio Quipar. The site was Middle Paleolithic and had a lot of lithic and microfaunal finds, the latter particularly interesting me as I was considering doing a project with them. The field crew was extremely nice – all of them spoke English extremely well, even though almost none of the student crew spoke Spanish – and the crew (roughly 20 people) got along very well.

It was an amazing experience to get hands-on training doing work, which including excavation and wet sieving mainly. The fieldwork took place in the morning, followed that afternoon by lab work classifying faunal remains. All of the work took place with the whole group, the team – which was mainly seniors and graduate students, but including underclassmen like me – got along really well and became one cohesive unit. Our days off were filled with trips to the local museum, nearby Murcia, and Spanish Levantine rock art in Moratalla.

Beyond getting practical experience, I feel that the best reason to go on to a field school or work on a site is to get to know other archaeologists and interested anthropologists as students. Most of the time at the site was down-time, which we filled with chatting about archaeology, interests, and other topics you can’t really bring up to your theater major roommate. I highly recommend going to field school to get a feel for the kind of work you’d be interested in doing, I know that it sealed the deal for me getting into archaeology.